What is this secret sin; this untold tale,

Horace Walpole, The Mysterious Mother (1768)

That art cannot extract, nor penance cleanse?

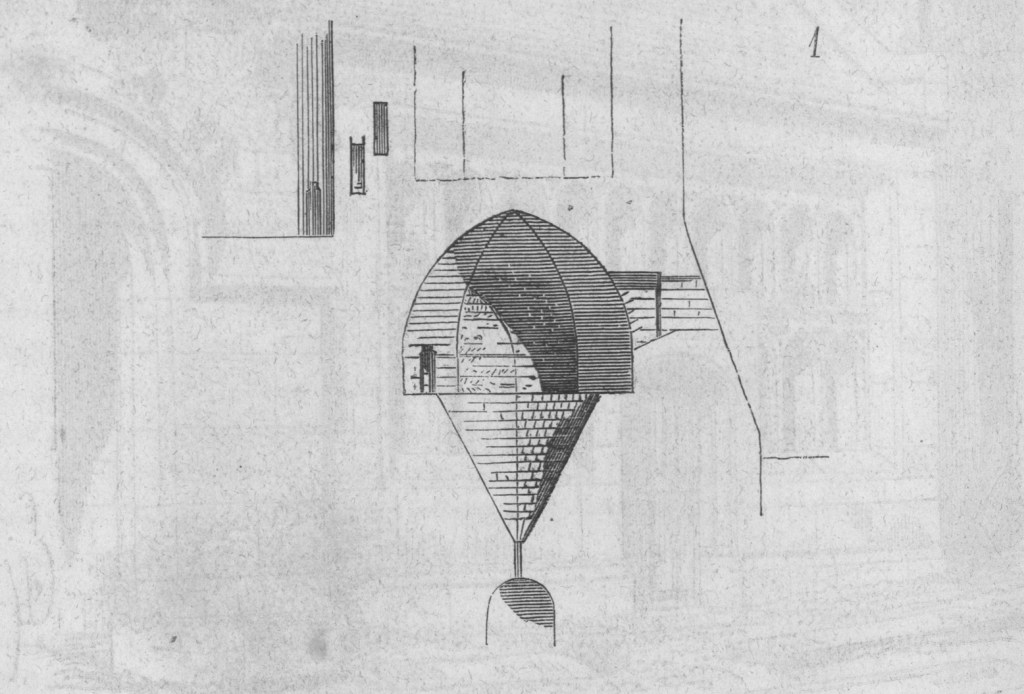

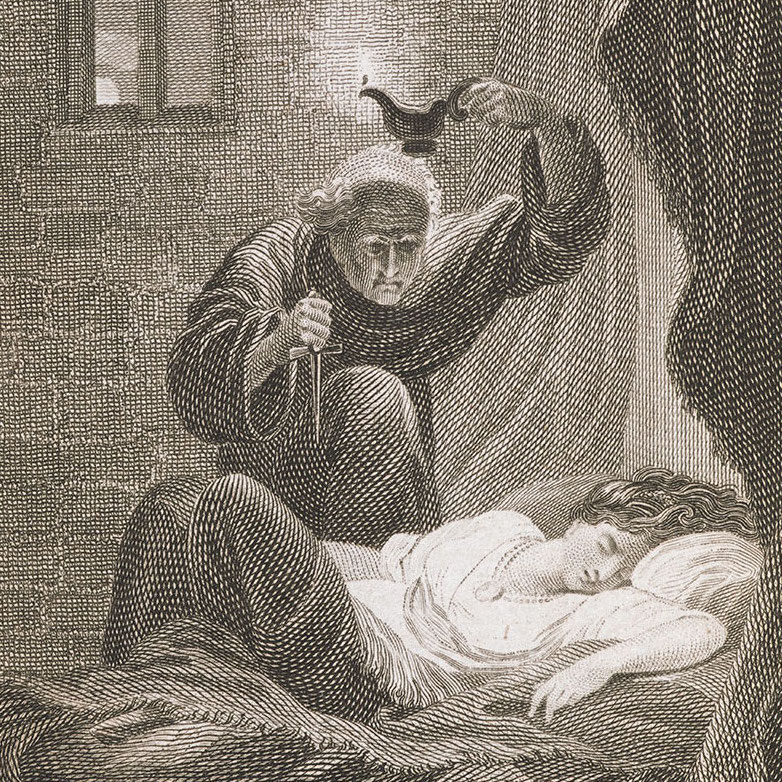

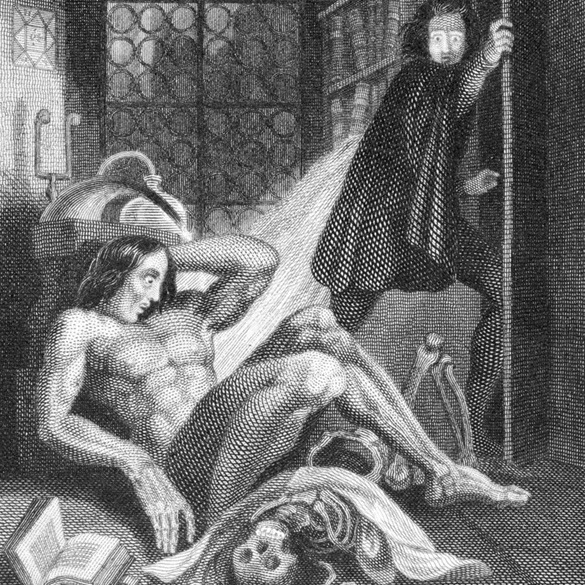

I work at the crossroads of Romanticism, the long eighteenth century (1660–1834), and the Black Atlantic. My dissertation, entitled Oubliette: The Atlantic Memory of a Portable Trope, investigates connections between Gothic fiction, slave narratives, and carceral figuration. In particular, it examines a tropology of carceral depth that first appeared in nonfiction period writing on the oubliette, a vertical dungeon that derives its etymology from the French oublier — to forget — and threatens the annihilation of an imprisoned subject. I identify the oubliette as a synthesis of the Gothic conventions of tyranny and live burial, examining the related use of flight and pursuit scenarios that involve networks of punitive power extending from tyrannical figures.

Such networks, I argue, share a structural logic with those found in narratives of enslaved Africans who, even when able to attain manumission, contended with the rampant practice of “trepanning”: abduction and recapture into slavery. At the centre of my analysis is the incorporation of this roving abuse of power into expressions of figurative depth that evoke carceral space, resulting in a portable trope that would define the convergence of Gothic and abolitionist writing during the Age of Revolution (1789–1848). The vertical structure of the oubliette provides the vehicle for this trope, the paradoxical function of which is the terrifying disappearance and abject preservation of its victims.

The pre-revolutionary foundations of this tropology lie in eighteenth-century nonfiction works of historiography, lexicography, and political theory. Based on archival research I have conducted at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the National Institute of Art History (Paris), and Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO), I track the quasi-folkloric iterability of this dungeon as authors repeatedly — often fancifully — deployed it in nearly one hundred manuscripts prior to 1789. The eighteenth-century imaginaire often associated the oubliette with Louis XI (1423–1483), his provost of the marshals Tristan L’Hermite (1405–1479), Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642), and the Bastille prison, yet references to its use also exhibit rhetorical hyperbole and outright mythmaking. It was this very mythopoetic development, however, that allowed authors of Gothic novels and Black autobiographies to adapt an architectural symbol of absolutism as a set of figurative and epistemological coordinates for various enormities. This inquiry does not conflate the respective exercises of power featured in Gothic and Black Atlantic texts; rather, it explicates the rhetorical transformation of the oubliette from an architectural symbol of ancien régime despotism to a metaphor responsive to the atrocities of a Gothicized Atlantic World.

I am also working on a book project examining maritime and terrestrial vehicles as discursive sites that informed a poetics of “mobilité immobile” (to borrow a phrase from Victor Brombert). This inquiry will expand the geography and topography of my research on the eighteenth-century mobility of prison forms. While the dissertation takes a number of trans-Atlantic texts into account — especially those concerning the West Indies in either fictive or documentary form — it nevertheless focalized British Romanticism’s uptake and dissemination of the oubliette trope. In the next phase of my research, I will address to a far greater extent the interpenetration of British, French, and early-American literature vis-à-vis Gothicized representations of transportation and its infrastructure.

This will include not only the slaving ships and Botany Bay-bound prisoner transports so notable in the period, but fictive characterizations of urban mobility such as William Godwin’s carceral rendering of carriages in Damon and Delia (1784); the spatial contradictions of empire that suffuse the incarceration of an enslaved African in Letter IX of J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur’s Letters from an American Farmer (1782); and the life and works of Pétrus Borel (1809–1859), who died in French Algeria (1830–1962) and whose Champavert: Contes Immoraux (1833) and Madame Putiphar (1839) evidence a carceral poetics that extends beyond the dungeon proper and across imperial networks. The project will reflect the geographic fluidity that suffused national literatures in the period, engaging what Joselyn M. Almeida has described as the literary “pan-Atlantic” and attending to relations between print culture and politico-economic conditions that, throughout the period, remained in a state of transport.