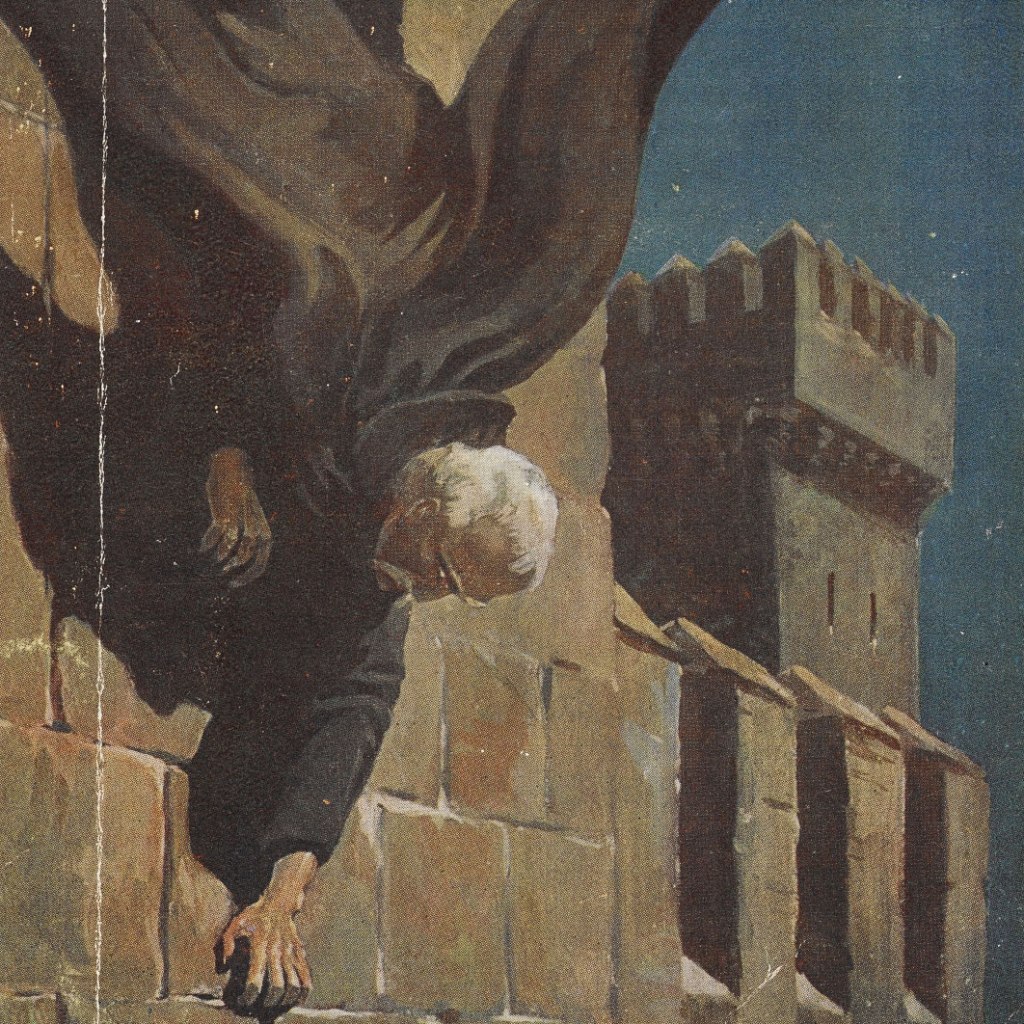

Welcome to my house. Come freely. Go safely; and leave something of the happiness you bring!

Bram Stoker, Dracula (1897)

What follows is a list of both academic and non-academic resources on topics related to the literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as well as literary study in general, for the use of students, colleagues, and curious readers everywhere. A chronology and lists of key terms and loci may be found below.

BLACK ATLANTIC

“Afro-Pessimism” (Oxford Bibliographies)

The Bigger 6 Collective

Billie Holiday (official website bibliography)

“Black Atlantic” (Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought)

“The Black Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions” (Oxford Bibliographies)

“Literature, Slavery, and Colonization” (Oxford Bibliographies)

“Mary Prince” (Margôt Maddison-Macfadyen)

North American Slave Narratives (Documenting the American South; University of North Carolina)

Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative (North American Slave Narratives)

“Phillis Wheatley” (Poetry Foundation)

“Slavery in British and American Literature” (Oxford Bibliographies)

“Timeline of Haitian History” (Wikipedia)

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (Harvard University)

ENGLISH MISCELLANY

The Alasdair Gray Archive

Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Bodleian Libraries (University of Oxford)

British Library

British Library English and Drama blog

The Call for Papers Website (University of Pennsylvania)

“Glossary of Poetic Terms” (Poetry Foundation)

The Harry Ransom Center (University of Texas at Austin)

Letters of Oscar Wilde (edited by Rupert Hart-Davis)

Library of America

Library of Congress

“List of Narrative Techniques” (Wikipedia)

Literary Studies Journals (Princeton)

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature

Poetry Foundation

Project Gutenberg

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (University of Toronto)

GOTHIC

“An Introduction to Ann Radcliffe” (The British Library)

The British Library’s Index of Articles on the Gothic

Bodleian Resources on Frankenstein

“Crime Fiction” (Oxford Bibliographies)

“Film Noir” (Oxford Bibliographies)

Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds (open access)

“The Ghost Story” (Oxford Bibliographies)

“Glossary of Literary Gothic Terms” (Douglass H. Thomson)

“Gothic Architecture” (Oxford Bibliographies)

“The Gothic: A Lecture by David Punter”

“Gothic Motifs” (The British Library)

“Gothic Revival/Gothick” (Oxford Bibliographies)

Gothic Studies (Edinburgh UP)

“Irish Gothic Tradition” (Oxford Bibliographies)

International Gothic Association (IGA)

Manchester Centre for Gothic Studies

Strawberry Hill House

Valancourt Books

“Vampire Fiction” (Oxford Bibliographies)

LITERARY THEORY; PHILOSOPHY

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

“Introduction to Theory of Literature” (Paul H. Fry; Open Yale Courses)

Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism

“Literary Theory” (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

“Literary Theory and Criticism” (Oxford Bibliographies)

“Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism” (Purdue OWL)

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

ROMANTICISM

“19th Century Romantic Aesthetics” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

“An Introduction to British Romanticism” (Poetry Foundation)

British Association for Romantic Studies (BARS)

The British Library’s Index of Articles on Romanticism

The Common Place: Romantic Women Writers Collection (Lindsey Seatter, Kwantlen Polytechnic)

Essays in Romanticism (Liverpool University Press)

European Romantic Review (Routledge)

Keats-Shelley Association of America

Keats-Shelley House

The London-Paris Romanticism Seminar

North American Society for the Study of Romanticism (NASSR)

Romanticism on the Net

“Scholarly Journals” (Romanticism on the Net)

“Romanticism” (Oxford Bibliographies)

Romantic Circles

The Shelley-Godwin Archive

Studies in Romanticism (JHUP; JSTOR)

“Timeline of the French Revolution” (Wikipedia)

The William Blake Archive

CHRONOLOGY

| 1066 | Norman Conquest of England |

| 1450 | Johannes Gutenberg’s moveable-type printing press in operation |

| 1688 | Glorious Revolution: James II of England (Catholic) and VII of Scotland deposed by William III of Orange (Protestant; James’s nephew) and Mary II (Protestant; James’s daughter) |

| 1689 | Toleration Act (Parliament of England) granted freedom of worship to nonconformist/dissenting Protestants; did not remove exclusions from political office and universities; did not apply to Roman Catholics, Jews, nontrinitarians, or atheists; allowed nonconformists/dissenters their own places of worship and schoolteachers |

| 1707 | Acts of Union (Union with Scotland Act in 1706 by the Parliament of England and the Union with England Act in 1707 by the Parliament of Scotland) united England and Scotland “into One Kingdom by the Name of Great Britain” |

| 1740 | “Rule, Britannia!” composed by James Thomson, set to music the same year by Thomas Arne, featuring the refrain, “Rule, Britannia! rule the waves: / Britons never will be slaves.” |

| 1742–45 | Edward Young, Night Thoughts |

| 1745 | Scottish rebellion at Culloden |

| 1762 | James Macpherson, Poems of Ossian |

| 1764 | Horace Walpole, The Castle of Otranto (Strawberry Hill printing) |

| 1765 | Bishop Thomas Percy, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry; Jonathan Strong ruling |

| 1768 | Walpole, The Mysterious Mother |

| 1772 | James Somerset ruling (English Court of King’s Bench) decided than an enslaved African on English soil could not be forced from the country (in this case to Jamaica) for sale |

| 1775 | battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19th ignited the American Revolutionary War, a colonial civil war between Crown loyalists and republicans that would last until 1783 |

| 1776 | United States Declaration of Independence |

| 1781 | Zong Massacre: mass killing of over 130 Africans aboard the slave ship Zong on a series of days following November 29th; the lives of the enslaved were insured on a policy taken out by the William Gregson syndicate; when drinking water ran low, the crew murdered the enslaved by throwing them overboard; the Zong‘s owners’ attempt to collect on the insurance, and the efforts of abolitionists such as Olaudah Equiano and Granville Sharpe to hold them accountable, made a cause célèbre of the massacre |

| 1782 | Hector St. John de Crèvecœur’s Letters from an American Farmer |

| 1783 | Zong massacre brought before the courts |

| 1784 | James Ramsay’s Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of African Slaves |

| 1786 | Thomas Clarkson’s Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species |

| 1787 | Assemblée des notables [Assembly of Notables] convened by French government to address growing financial crisis; Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species |

| 1789 | Prise de la Bastille [storming of the Bastille] and the “Grande Peur” [Great Fear]; Déclaration des droits de l’Homme et du citoyen [Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen]; Equiano, The Interesting Narrative; Radcliffe, A Sicilian Romance |

| 1790 | Fête de la Fédération [Festival of the Federation] held on the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille; Helen Maria Williams’s Letters Written in France published in London later that year |

| 1791 | Revolution in St. Domingue; revised, shortened edition of Thoughts and Sentiments; Radcliffe’s The Romance of the Forest; Sade’s Justine; Olympe de Gouges’s Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne [Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen] |

| 1792 | foundation of the French First Republic (1792–1804) |

| 1794 | Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho |

| 1796 | Matthew G. Lewis, The Monk |

| 1797 | Radcliffe, The Italian |

| 1798 | William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads |

| 1800 | Lyrical Ballads second edition, includes preface |

| 1802 | Lyrical Ballads third edition, includes expanded preface |

| 1804 | foundation of the first French Empire (1804–1815 with interruption between May 3, 1814 and March 20, 1815) |

| 1806 | Charlotte Dacre, Zofloya |

| 1807 | British Abolition Act outlaws slavery in Britain; U.S. Congress outlaws Americans’ participation in the African slave trade |

| 1814 | Sir Walter Scott, Waverley |

| 1818 | Mary Shelley, Frankenstein |

| 1819 | John William Polidori, The Vampyre; John Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” “Ode on Indolence,” “Ode on Melancholy,” “Ode to a Nightingale,” “Ode to Psyche,” “To Autumn” |

| 1820 | Charles Maturin, Melmoth the Wanderer |

| 1824 | James Hogg, Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner |

| 1831 | Frankenstein popular edition; The History of Mary Prince |

| 1833 | British Emancipation Act outlaws Britain’s worldwide participation in all aspects of African slavery |

| 1848 | the “Springtime of the Peoples,” a series of revolutions against reactionary monarchical regimes across Europe, takes place over the course of more than a year between 1848 and 1849; foundation of the French Second Republic (1848–1852); the Fox sisters (Leah, Margaretta, and Catherine) move with their family into an ill-reputed house in Hydesville, New York; they soon begin a fraudulent career as “mediums,” claiming to commune with an entity they first refer to as “Mr. Splitfoot” (ie. the Devil) and later as the spirit of a murdered pedlar buried in the basement; the sensation around their claims gives rise to the new religious movement of Spiritualism; among its adherents would be Arthur Conan Doyle |

| 1850 | Lucy Sessions, graduating with a literary degree from Oberlin College, Ohio, becomes the first black woman in the U.S. to receive a college degree |

| 1852 | foundation of the French Second Empire (1852–1870) |

| 1870 | foundation of the French Third Republic (1870–1940) |

| 1882 | Society for Psychical Research (S.P.R.) founded in London; earnest intellectuals in pursuit of scientific documentation of the supernatural; fuelled by the cultural vogue of the Spiritualism movement |

| 1888 | sex workers Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly are found murdered in Whitechapel, London; murders attributed to “Jack the Ripper” after signature to the “Dear Boss letter” received by Central News Agency of London |

| 1897 | Bram Stoker, Dracula |

| 1899 | Ada Goodrich-Freer and John, Marquess of Bute, The Alleged Haunting of B—— House; this Spiritualist-inspired account of Goodrich-Freer’s temporary residence at Ballechin House in Perthshire, Scotland, backed by the Society for Psychical Research,served as the inspiration for Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House |

| 1935 | Arthur Evans, The Palace of Minos |

| 1946 | foundation of French Fourth Republic (1946–1958) |

| 1948 | Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” published in the New Yorker |

| 1955 | Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley |

| 1958 | foundation of French Fifth Republic (1958–present) |

| 1959 | Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House |

TERMINOLOGY

| Abaddon | the Hebrew term Abaddon (Hebrew: אֲבַדּוֹן ’Ăḇaddōn, meaning “destruction”, “doom”), and its Greek equivalent Apollyon (Koinē Greek: Ἀπολλύων, Apollúōn meaning “Destroyer”) appear in the Bible as both a place of destruction and an angel of the abyss; in the Hebrew Bible, abaddon is used with reference to a bottomless pit, often appearing alongside the place Sheol (שְׁאוֹל Šəʾōl), meaning the resting place of dead peoples |

| aisthēsis | etymologically and conceptually linked with sense perception (as opposed to, in the Platonic tradition, noēsis or intellection) in ancient, medieval, and early-modern thought, aisthēsis formed part of theorizing not only questions surrounding beauty and art, but also perception, epistemology, and even ontology (in, for instance, the work of Plato, Aristotle, and Thomas Aquinas); during the Enlightenment and its project of subdivision and categorization of the humanities, aisthēsis became subsumed, in the work of Alexander Baumgarten, by “aesthetics,” the study of beauty in the narrower sense; however, by the beginning of the 20th century and the Marxist/Freudian/Saussurean revolution in humanist inquiry and the “avant-garde” revolution in the arts, aisthēsis resumed its place and function as a central node in a vast network of concerns: for the Marxists, the history of aisthēsis follows the pattern of social development of progressive mastery over nature by humankind, described as a process of rationalization (the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory); in psychoanalysis and phenomenology, artistic activity is regarded as the “sublimated” expression of socially objectionable energies, taking place in a world conceived of as indefinite and open multiplicity (John Dewey, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, et al.); in poststructuralist theory, the image not simply “acquires” a politico-aesthetic function by way of an act of judgement, but rather accedes in its very technological condition to a political imaginary, to an aesthetics as such (Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, et al.) |

| amende honorable | “honourable penalty”; a mode of punishment in France that required the offender, barefoot and stripped to his shirt, and led into a church or auditory with a torch in his hand and a rope round his neck held by the public executioner, to beg pardon on his knees of his God, his king, and his country; abolished in 1791 and then again in 1830 after a brief revival |

| apophenia | the tendency to see meaningful patterns or connections between unrelated or random things |

| aposiopesis | from the Greek for “becoming silent,” a figure of speech wherein a sentence is deliberately broken off and left unfinished, the ending to be supplied by the imagination, giving an impression of unwillingness or inability to continue; e.g. “Get out, or else—!” |

| atopia | a concept describing the ineffability of things or emotions that are seldom experienced, that are outstanding and original in the strictest sense |

| ballad | a popular narrative song passed down orally; in the English tradition, it usually follows a form of rhymed (ABCB or ABAB) quatrains alternating four-stress and three-stress lines; folk (or traditional) ballads are anonymous and recount tragic, comic, or heroic stories with emphasis on a central dramatic event; examples include “Barbara Allen” and “John Henry”; beginning in the Renaissance, poets have adapted the conventions of the folk ballad for their own original compositions; examples of this “literary” ballad form include John Keats’s “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” Thomas Hardy’s “During Wind and Rain,” and Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee” |

| capriccio | a genre of visual art featuring fantastical, dream-like compositions of impossible or composite buildings; emerged during the Renaissance, revived in the eighteenth century |

| chemins de Jérusalem | Christian term sometimes used for labyrinths, particularly those placed as a site of symbolic pilgrimage in medieval churches, especially in northern France |

| coenesthesia | the general feeling of inhabiting one’s body that arises from multiple stimuli from various bodily organs; feelings of health, illness, rigour, fatigue as sensed bodily |

| conspicuous consumption | the term describes and explains the consumer practice of buying and using goods of a higher quality, price, or in greater quantity than practical; in 1899, the sociologist Thorstein Veblen coined the term conspicuous consumption to explain the spending of money on and the acquiring of luxury commodities (goods and services) specifically as a public display of economic power—the income and the accumulated wealth—of the buyer; to the conspicuous consumer, the public display of discretionary income is an economic means of either attaining or maintaining a given social status |

| elegy | in traditional English poetry, an elegy is often a melancholy poem that laments its subject’s death but ends in consolation; in the 18th century, the “elegiac stanza” emerged, though its use has not been exclusive to elegies; elegiac stanza is a quatrain with the rhyme scheme ABAB and written in iambic pentameter |

| epic | a long narrative poem in which a heroic protagonist engages in an action of great mythic or historical significance. Notable English epics include Beowulf, Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (which follows the virtuous exploits of 12 knights in the service of the mythical King Arthur), and John Milton’s Paradise Lost, which dramatizes Satan’s fall from Heaven and humankind’s subsequent alienation from God in the Garden of Eden; relatedly, Mock-heroic, mock-epic or heroi-comic works are typically satires or parodies that mock common Classical stereotypes of heroes and heroic literature |

| epigram | a pithy, often witty, poem |

| epitaph | a short poem intended for (or imagined as) an inscription on a tombstone and often serving as a brief elegy |

| fable | a literary genre defined as a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a particular moral lesson, which may at the end be added explicitly as a concise maxim or saying |

| the fantasy of the absurd | a phrase used by François Truffaut in his extensive interviews with Alfred Hitchcock, as recorded in Le Cinéma selon Alfred Hitchcock (1966), to describe the gratuity that characterizes the director’s best work: “The most appealing aspect of that sequence with the plane [in North by Northwest (1959)] is that it’s totally gratuitous—it’s a scene that’s been drained of all plausibility or even significance. Cinema, approached this way, becomes truly abstract art, like music. And here it’s precisely that gratuity, which you’re oten criticized for, that gives the scene all of its interest and strength. . . . How can anyone object to gratuity when it’s so clearly deliberate—it’s planned incongruity? It’s obvious that the fantasy of the absurd is a key ingredient of your filmmaking formula” (256). |

| fragment | a partial, incomplete, or broken-off work; the vogue for these in the Romantic Age |

| frénétique | “frenetic”; early nineteenth-century French term of abuse for novels characterized by melodrama and shock-tactics; contributors include Hugo and early Balzac |

| georgic | a poem or book dealing with agriculture or rural topics, which commonly glorifies outdoor labor and simple country life; often takes the form of a didactic or instructive poem intended to give instructions related to a skill or art; the Roman poet Virgil famously wrote a collection of poems entitled Georgics, which has influenced poets since |

| hymn | a poem praising God or the divine, often sung; in English, the most popular hymns were written between the 17th and 19th centuries |

| irony | the expression of one’s meaning by using language that normally signifies the opposite, typically for humorous or emphatic effect (OED); ‘irony’ comes from the Greek eironeia (εἰρωνεία) and dates back to the 5th century BCE, coined in reference to a stock-character from Old Comedy (such as that of Aristophanes) known as the eiron, who dissimulates and affects less intelligence than he has, and so ultimately triumphs over his opposite, the alazon, a vain-glorious braggart; although initially synonymous with lying, in Plato’s dialogues eironeia came to acquire a new sense of an intended simulation the audience or hearer was meant to recognize; literary theory and criticism has contending definitions of irony, but four general categories have emerged: verbal irony (a statement in which the meaning that a speaker employs is sharply different from the meaning that is ostensibly expressed), dramatic irony (which provides the audience with information of which characters are unaware, thereby placing the audience in a position of advantage to recognize their words and actions as counter-productive or opposed to what their situation actually requires), cosmic irony (sometimes also called “the irony of fate”, presents agents as always ultimately thwarted by forces beyond human control), and romantic irony (closely related to cosmic irony, and sometimes the two terms are treated interchangeably, yet distinct, however, in that the author assumes the role of the cosmic force) |

| labyrinth | a tortuous structure; sometimes a maze; may be unicursal (one elaborate route to the centre) or multicursal (multiple routes, tricks, and dead ends designed to bewilder or entertain); strong association with ancient Minoan myth of King Minos’s labyrinth, built by Dedalus to confine the monstrous spawn of Minos’s wife, Pasiphae, and a bull: the Minotaur; according to this myth, a tribute of young Greeks was sacrificed to the Minotaur’s hunger inside the labyrinth; Theseus, one such tribute, was aided by Ariadne, Minos’s daughter, with a sword to kill the monster and a thread to navigate his way back to freedom; recorded in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid; labyrinths would later feature in Walpole’s Otranto and myriad Gothic narratives that followed, including in the envelope structure and epistolary narration of novels such as Melmoth the Wanderer, Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights, and Dracula |

| litotes | ironic understatement by which an affirmation is expressed in its negative: “you won’t be sorry” |

| lyric | a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person; the term for both modern lyric poetry and modern song lyrics derives from the Ancient Greek lyric, which was defined by its musical accompaniment, usually on an instrument known as a kithara, a seven-stringed lyre (hence “lyric”); these three are not equivalent, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode and Ancient Greek lyric poetry was typically chanted verse |

| märchen | German term for fairy tale |

| metaphor | comparison by means of direct substitution; in a metaphor, a word or expression that in literal usage denotes one kind of thing is applied to a distinctly different kind of thing, without asserting a comparison (as in a simile, which uses a connective such as “like” or “as”); a metaphor is composed of two elements, the metaphorical term and the subject to which it is applied; I. A. Richards introduced the name “tenor” for the subject and the name “vehicle”for the metaphorical term itself; a mixed metaphor conjoins two or more obviously diverse metaphoric vehicles; a dead metaphor is one which, like “the leg of a table” or “the heart of the matter,” has been used so long and become so common that its users have ceased to be aware of the discrepancy between vehicle and tenor |

| modern romance | eighteenth-century term for Gothic novels |

| nominalization | nominalizations are nouns that are created from adjectives (words that describe nouns) or verbs (action words); for example, “interference” is a nominalization of “interfere,” “decision” is a nominalization of “decide,” and “argument” is a nominalization of “argue” |

| numen | the spirit or divine power presiding over a thing or place |

| object narrative | also known as “it-narrative” or “novel of circulation”; sub-genre of the novel that makes use of a material object, such a coin, as a structural conceit; the fortune of the object is the narrative’s focus; examples include Joseph Addison’s Adventures of a Shilling (1710), Charles Johnstone’s Chrysal; or, The Adventures of a Golden Guinea (1760–1765), and Tobias Smollett’s The History and Adventures of an Atom (1769) |

| ode | odes are elaborately structured poems praising or glorifying an event or individual; a classic ode is structured in three major parts: the strophe, the antistrophe, and the epode |

| oratorio | a musical composition with dramatic or narrative text for choir, soloists and orchestra or other ensemble; like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters (e.g. soloists), and arias; however, opera is musical theatre, and typically involves significant theatrical spectacle, including sets, props, and costuming, as well as staged interactions between characters. In oratorio, there is generally minimal staging, with the chorus often assuming a more central dramatic role, and the work is typically presented as a concert piece |

| oubliette | a vertical dungeon, deep enough to render unassisted escape impossible, into which a prisoner could be lowered, covered with a trap-door, and effectively forgotten; actual historical examples of the oubliette are generally dubious, but, like the “iron maiden” and other pseudo-historical instruments of torture, it acquired substantial cultural significance with the rise of modern antiquarianism; the etymology of the word contains a range of psychological, political, and spatial associations; “oubliette” is suggestively tied to the French verb oublier [to forget] as well as the generic noun cachot for any type of dungeon or prison, and in francophone spheres remains an idiomatic expression for the impulse to forget something, usually an unpleasant task one wishes to postpone; the Oxford English Dictionary, which defines oubliette as “a secret dungeon with access only through a trapdoor in its ceiling,” traces the word’s etymology to oublier in Middle French and oblider in Old French, the latter a “vulgar Latin derivative of classical Latin oblīviscī,” which is itself linked to the Latin borrowing “obliviscence” [forgetting] and the Franco-Latin borrowing “oblivion”; the Grand Robert foregrounds the oubliette’s temporal implications, defining it as a “cachot où l’on enfermait les personnes condamnées à la prison perpétuelle” [a dungeon in which one encloses those condemned to perpetual imprisonment]; this entry also includes the idiom “mettre en oubliette” [to put in an oubliette], meaning “laisser de côté, refuser de s’occuper de (qqn ou qqch.)” [to set aside, refuse to consider (someone or something)]; “cachot” derives from “cacher” [to hide]; the oubliette is a trope of Revolutionary writing on the ancien régime; instances of its deployment in fiction range from the Romantic novel of the 1790s to the late-twentieth-century detective fiction of Thomas Harris |

| palinode | an ode in which the writer retracts a view or sentiment expressed in an earlier poem |

| patrimoine | heritage; French historico-cultural concept denoting the national sense of legacy and the public/institutional initiatives to construct and preserve it |

| pharmakos | a pharmakos was a person or animal sacrificed or exiled in ancient Greece as a scapegoat to atone for or purify a community or city; derived from Ancient Greek pharmaco- for “medicine” with alteration of accent and gender: the scapegoat representing a personified remedy; closely related to “pharmakon,” a word that can variously mean remedy, poison, or scapegoat, and that features prominently in Jacque Derrida’s “Plato’s Pharmacy” |

| pointed arch | architectural motif of western-European Gothic architecture; originally a medieval French borrowing from ancient Syrian Islamic and Christian examples |

| ruinenlust | the desire for ruins (ruin-gazing) |

| ruinensehnsucht | the longing or yearning for ruins (ruin-gazing) |

| ruin porn | a sub-genre of photography of abandoned and ruined structures, often used as horror-film locations; strongly associated with twenty-first-century Detroit, Michigan |

| satire | a genre of the visual, literary, or performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposing or shaming the perceived flaws of individuals, corporations, government, or society itself into improvement; satirical literature can commonly be categorized as either Horatian, Juvenalian, or Menippean; Horatian satire, named for the Roman satirist Horace (65–8 BCE), playfully criticizes some social vice through gentle, mild, and light-hearted humour; Juvenalian satire, named for the writings of the Roman satirist Juvenal (late first century–early second century AD), is more contemptuous and abrasive than the Horatian; Menippean satire, named after the third-century-BC Greek cynic parodist and polemicist Menippus, is characterized by attacking mental attitudes rather than specific individuals or entities |

| simulacrum | from Latin simulacrum, meaning “likeness, semblance”; a representation or imitation of a person or thing; Jean Baudrillard argues in Simulacra and Simulation that a simulacrum is not a copy of the real, but becomes truth in its own right: the hyperreal; according to Baudrillard, what the simulacrum copies either had no original or no longer has an original, since a simulacrum signifies something it is not, and therefore leaves the original unable to be located |

| shauerroman | “shudder novel” |

| topos | in classical rhetoric, the term for recurrent poetic concepts or formulas (from the Ancient Greek (τόπος κοινός tópos koinós) for “commonplace,” sometimes translated as “topic,” “theme,” or “line of argument”; rhetorically speaking, a locus for argumentation; in literary theory and criticsm, a conspicuous element, such as a type of incident, device, reference, or formula, which occurs frequently in works of literature; the modern popular usage of “trope” has come to supplant this sense of the term |

| trope | a figure of speech which consists in the use of a word or phrase in a sense other than that which is proper to it, hence, more generally, a figure of speech; figurative or metaphorical language (OED); borrowed from Latin tropus “figure of speech” (Medieval Latin, “embellishment to the sung parts of the Mass”), borrowed from Greek trópos “turn, way, manner, style, figurative expression,” noun derivative from the base of trépein “to turn”; Kenneth Burke identifies metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony the “four master tropes” (A Grammar of Motives); a semantic shift has taken place in popular usage whereby “trope” is often used to refer to a recurring motif, device, narrative formula, or cliché, what is properly designated a “topos” in traditional theory and criticism |

TOPOGRAPHY

| Le Conciergerie | former courthouse and prison; during the French Revolution, 2,780 prisoners, including Marie-Antoinette, were imprisoned, tried and sentenced at the Conciergerie, then sent to different sites to be executed via guillotine; the prison features in Ann Radcliffe’s The Romance of the Forest (1791) as the site of Pierre de la Motte’s imprisonment |

| Fonthill Abbey | William Beckford’s faux-medieval megastructure; funded by slavery profits from the Jamaican sugar plantations he inherited |

| Hampton Court Palace | the Hampton Court maze, commissioned by William III in 1690, sits on its grounds; oldest surviving hedge maze in Britain |

| Monastery of Santa Maria at Batalha | enormous Gothic structure in Portugal |

| Palace of Westminster | British Houses of Parliament rebuilt in a Gothic-revival style |

| Strawberry Hill | Horace Walpole’s fanciful antiquarian construction |

| Tintern Abbey | famed ruins; subject of J. M. W. Turner’s painting and Wordsworth’s “Lines Written Above Tintern Abbey” |

| Westminster Abbey | Gothic-revival cathedral in London; burial site of the monarchy and many notables |

| Youlbury House | Arthur Evans’s vast country house, designed as a labyrinth |

| Chartres cathedral | notable labyrinth in the floor of the nave |

| Château de Coucy | ruins of a castle in the commune of Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique, in Picardy, built in the 13th century and renovated by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc in the 19th century; destroyed with dynamite by German forces after its occupation during WWI; said to contain an oubliette |

| Château de Pierrefonds | castle situated in the commune of Pierrefonds in the Oise department in the Hauts-de-France region; built in the 12th century and renovated by Viollet-le-Duc; said to contain several oubliettes |